Update by Brandon Adler, Literal Task Master

Welcome to my world...

As a producer, one of my jobs is creating and understanding the game's master schedule. It's a never-ending task that requires constant refinement and adjustment. Anything that is added or changed can cause a cascade of unintended consequences which is why as game developers we have a responsibility to vet everything that goes into the game.

Today I'd like to give you a glimpse into how we approach game development from a scheduling perspective and what our typical thought processes are when figuring this stuff out. You will be able to see how each part of our area creation fits into the schedule and why changes and modifications can lead to difficult decisions for the team. Hopefully, it will give a bit more insight into the tough decisions that we make each day when crafting Project Eternity.

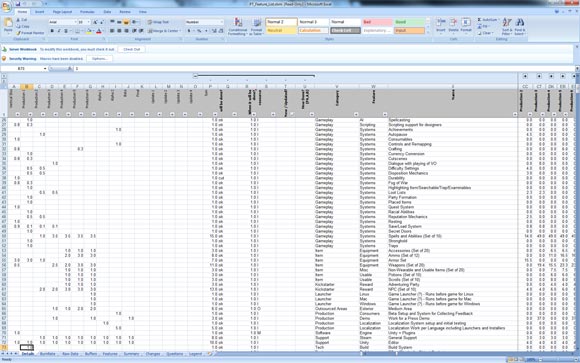

The Schedule

One thing to remember is that when we are in the middle of production the schedule has already been created for just about everything in the game. What I mean by this is that we have identified all of the major tasks that will need to be accomplished and allotted time and resources in our budgets to match those tasks.

Depending on the team's familiarity with the type of game we are creating, this can mean anywhere from a tiny bit of guesswork to larger amounts of... estimation. With Eternity we are very familiar with what it takes to make an isometric, Western RPG with branching dialogues and reactivity. It's Obsidian's bread and butter. Because of this our initial estimates are good approximations.

Since most of our features and assets are budgeted at the start of the project, any changes to those items have to be accounted for in the schedule. This can mean a few different things - anything from reducing time spent on other tasks, to changing previously scheduled items, to outright cuts - and when changes need to happen project leads consult with each other to try and figure out the best option. Keep this in mind when I start talking about changes to features and assets later on in this update.

One Small Interior Dungeon

Alright, let's stop talking in generalities and get into the meat of what it takes to create a first pass area in Eternity. I'll discuss a generic small interior dungeon area.

This area will have the following characteristics and constraints:

- Uses an existing "tileset." We don't have tiles in Eternity, but we do have sets of areas that share similar assets.

- Will have one unique visual feature in the area. This visual feature is something that will make the area stand out a bit. It doesn't have to be incorporated into the design, but we may want to do that to get the most bang for the buck.

- An Average complexity quest uses this area. "Average" is a flavor of quest in Project Eternity. It refers to the overall complexity of the quest. Quest complexity is determined by the amount of dialogue, branching, and steps a quest has.

- This is a 3x3 interior. A 3x3 interior is the equivalent of a 5760x3240 render. An easier way to think about it is that a 3x3 area is nine 1920x1080 screens worth of content. You can imagine that making an area even a tiny bit larger can actually lead to enormous amounts of work. As an example, a 3x3 is nine screens of work, where a 4x4 is 16 screens of work... almost double the number of screens.

To create our small interior dungeon area, the following has to occur:

- An area designer (Bobby Null, for example) puts together a paper design for the area. This is usually part of a larger paper design, but for this purpose we can say that it is a separate element. For a small area like this, a paper design wouldn't take more than a quarter of a day.

Material concepts for a high wealth interior.

- After the paper design is constructed, it is passed to the area design team for revisions and approval. For the most part, this goes fairly quickly and normally wouldn't take more than a quarter of a day for a small area.

- A concept artist (Hi, Polina and Kaz) creates a concept for the unique visual element of this area. Let's say for our purposes the unique element is a cool adra pillar that is holding up a portion of the ceiling. This takes half a day to a day, depending on prop complexity. This may seem like a luxury, but making sure that the areas feel cohesive can save lots of revision time down the road.

- After the concept work is completed, it is reviewed by the Art Director (Rob Nesler) and the Project Director (Josh Sawyer). Any necessary changes are then made before being approved. Overall, it probably takes about a quarter of a day for review and any revisions that need to be done.

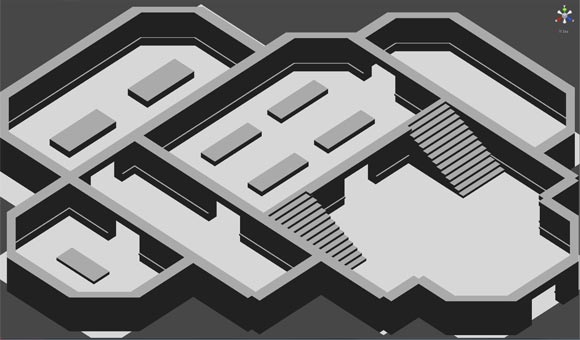

An initial pass on a blockout before it has had a review.

- After the paper design and concepts, an area designer creates a 3D blockout of the area in Unity. This allows the designer to walk through the area and make sure it flows well. This also helps to give the environment artist assigned to the area an idea of where the various elements should be laid out. A full blockout of a 3x3 area normally wouldn't take more than half a day. This is an extremely important part of the process. Sometimes an area seems great on paper, but in practice it is clunky or frustrating.

- Once the blockout is finished it's passed along to the area strike team for review. The area strike team includes people from most disciplines. This is the point where revisions are performed and the layout becomes finalized. The changes can be as simple as moving some props around or as complicated as redesigning major portions of the layout. Again, for a small area of this size, we aren't looking at more than half a day for all of the feedback and revisions.

- With the blockout in place, the area can move to environment art (For example, Hector "Discoteca" Espinoza) for the art pass. This includes putting together existing pieces and creating new assets to make the area. A large portion of time allotted to an area is spent in environment art. A 3x3 area that uses mostly existing assets would typically get three days of environment art work, but, because we want to have a cool, unique piece in the area we will add about a day of environment art time. This gives a total of four days for the initial art pass.

- Like the blockout, the art pass is usually reviewed by the area strike team. Revisions can vary wildly depending on how everyone feels about the area, but it isn't uncommon for another quarter to half a day to be spent on review and revisions for this size of area.

The blockout above with revisions, 2D render, and initial design.

- Now with the 2D render in place, the area is ready for the real design work to be done. An area designer will typically get about three days to do the first pass on the area. This includes things like a loot pass, encounters, trigger setup, temp dialogs, etc.. Because this area has a quest that is running through it, though, it will get an extra day to work out all of those kinks. That puts us at four days for an initial design pass on the area.

- Remember the part about this area having a quest? Well, now is when a creative designer (Like Mr. Eric Fenstermaker, for example) comes through to write the dialogs. To be completely honest, this usually comes much later, but it works for our purposes. The narrative designer creates the NPC dialogs, quest dialogs, and companion interjections for the area. Usually an area designer will stub these conversations out and the narrative designer will come in and complete them. Depending on the amount of dialog this should take around a day or two for everything.

- Finally, a concept artist will take a pass at painting over the final 2D render. This pass is used for "dirtying up" an area and adding in the little details that might be difficult for an environment artist to create. As an example, we can cover up texture seems, add in variation on repeating textures, paint in lighting highlights, and even add things like patina or moss on objects. Due to Photoshop magic from Kaz, we can even propagate those changes into our diffuse maps so they show properly in any dynamic lights. This is a fairly low cost procedure and Kaz can cover a small area like this in about half a day.

- There are other considerations (Like animation, sound effects and visual effects, for example), but we will stop for now.

So, for those keeping count at home, to get a first pass area that is borderline Alpha (as in no bug fixing or polish work) it costs the project about 13 man days. This is little over one half of a man month of time for a small, simple area. Larger areas with more content take significantly longer to develop.

Our time estimations used for scheduling are determined in preproduction (prepro) phase. Our vertical slice (the end of prepro) is the culmination of the team identifying what it will take to make the game and then actually doing it. We get these numbers by seeing how long it takes the team to perform those tasks in our prepro, and then we can extrapolate those numbers over the course of the time we have budgeted to understand how much work can get done.

Tough Choices

A milestone will have 15 to 20 areas of varying complexity going at a time. A minor change in an area can cause a domino effect that starts schedule slippage. Remember that on a small team like Project Eternity we have a limited number of people that can work on any one part of the game so taking someone off of their current task to work on changes can gum up our pipelines and prevent others from completing their tasks. We can get around that by switching up the tasking, but it can quickly get out of hand and lead to inefficiencies.

That being said it's the team's responsibility to give our backers what they have paid for. If we are playing though part of the game and something feels off from what we promised to our fans, we need to seriously consider making changes - even if it pushes us off schedule. There have been times where an update leads to some serious discussion on the forums and within the team about a direction change. Ultimately all of that gets added into the equation as well.

Taking that into consideration, the team has to make difficult choices every day. Do we go through and do another prop pass on a level? What does that cost us in the long run? Will we lose an entire area in the game? These are questions that the leads struggle with everyday. We are always weighing the cost of assets and features against everything that still needs to get done.

Luckily, like I mentioned above, we have a bunch of smart, talented, experienced people working on Eternity. The pitfalls we have experienced in previous games give us a leg up when we are trying to navigate this project's development. I wanted to send out this update to give the fans a little insight into our daily processes and demystify what probably seem like arcane decisions. If you enjoy these types of updates, let me know in the forums and I will try to write more of them for you.